Many books have been published claiming to expose cryptographic evidence that Francis Bacon wrote Shakespeare [1,2]. Many of these are also totally unconvincing, often presenting deciphered gibberish or "codes" that can be found anywhere [3]. Here is a summary of some of the ciphers that are very likely to be intentional, and relatively easy to understand.

The first suspicion of ciphers may be aroused by noticing where the word Bacon appears in the First Folio. It appears only twice in the whole folio, once in Comedies, and once in Histories. Both times on page 53 [4].

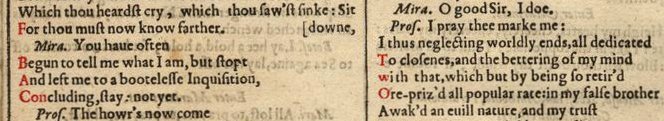

The first credible cipher is found on page two of the Folio, in the play “The Tempest” [5,6]:

Here, F BACon is found about half way down the page. The cipher seems to be indicated by the incorrectly cased w in the second column. The rational reader, however, needs more proof than this to be impressed.

On page 49 of Histories, in “1 Henry IV”, there is another acrostic, spelling out FBACO [6]:

This time, the cipher runs upwards. There is a TWO again, further up on the page. Of course, this is all still not convincing. Page 346 in “Antony and Cleopatra” has a similar acrostic cipher and TwO reappears [8]:

Intellectuals may complain that reading only the first letters of each line produces BAC, not BACON. The following cipher on page 143 of “Loves Labour's Lost” has an interesting twist [7]:

C is here substituted by three, presumably because it is the third letter of the alphabet. A=1, B=2, C=3, ...

Encrypted phrases are more valuable than single words, and page 131 in “2 Henry VI” delivers [6]:

BASTAW BACAn is too long to be coincidental, but is also strangely spelled. The previous cipher, however, contains the key. W is letter number 21 of the seventeenth century English alphabet, and exactly equal to 17+4 or R+D. Perhaps to confirm the presence of a cipher on the page, five occurrences of Lord are perfectly positioned along a straight line.

[2012 update] The TwO on page 2 may hint to the equation Two=B. In fact, Acon "sans b" can be found a few lines further down [6]:

Acon is preceded by two As that can be summed together to give A+A=1+1=2=B. But in addition to the expected BAcon, the name ALBAN also appears [9]! That two related words are revealed in one decipherment supports the validity of the method.

Finally, one last argument against BACon being chance. By searching electronically, only four BACons can be found in the Folio, two going going down (B-A-Con), and two going up (Con-A-B). The first one is on page 2 of Comedies. The three parts of the First Folio (Comedies, Histories, Tragedies) are paginated individually, which is why it is probably significant that one of the others is on page 2 of Tragedies [8]:

It should be pretty evident that there are indeed ciphers in the First Folio, only a few of them are shown here. The meaning and origin of the ciphers is, of course, debatable.

References

1 Owen, Orville Ward. (1893-5). Sir Francis Bacon's Cipher Story. Detroit: Howard Publishing.

2 Gallup, Elizabeth Wells. (1899). Biliteral Cypher of Sir Francis Bacon.

3 Friedman, William F. & Friedman Elizabeth S. (1957). The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

4 Donnelly, Ignatius. (1888). The Great Cryptogram. Chicago: R. S. Peale & Co.

5 Hall, Manly Palmer. (1928). The Secret Teachings of All Ages.

6 Loe, Erlend & Amundsen, Petter. (2006). Organisten. Oslo: J.W. Cappelens Forlag.

7 Eriksen, Kjell (Producer), & Friberg, Jørgen (Director). (2009). Shakespeares skjulte koder - Sweet swan of Avon [Television series DVD]. Norway: Videomaker.

8 Richard Tingstad. (2010). Summary of most convincing Bacon ciphers in Shakespeare. rictin.com.

9 Nate E. Shebell. (2012). Petter Amundsen, Oak Island and the Treasure Map in Shakespeare - Part I. wordpress.com.

By Richard Tingstad, 2010